LOADING

Bolivar Peninsula Texas

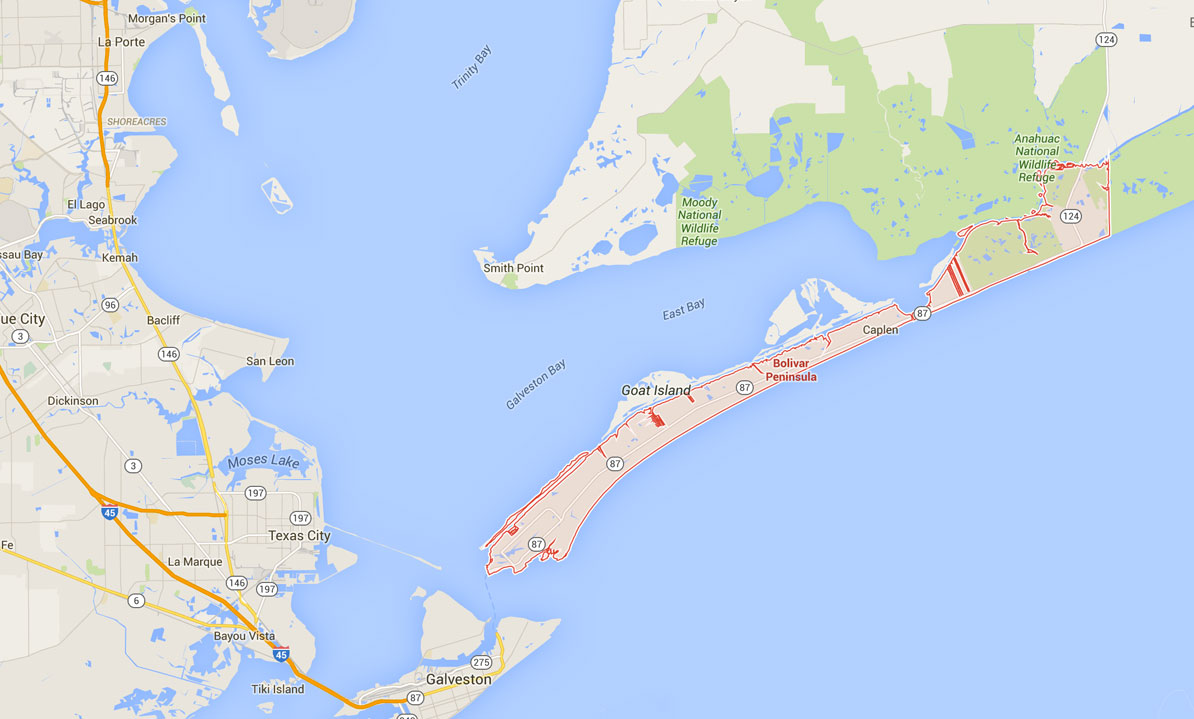

Bolivar Peninsula, named for Simón Bolívar (1783–1830), the South American hero, is a narrow strip of eroding land or "barrier island" stretching twenty-seven miles along the Texas Gulf Coast in a northeasterly direction to form eastern Galveston County (the center of the peninsula is at 29°26' N, 94°41' W). At its widest point between Crystal Beach and Caplen, the peninsula is three miles wide. At its narrowest point is the community of Gilchrist, where the peninsula is a quarter of a mile wide. Water separates the peninsula from Galveston Island by a distance of less than three miles. The sheltered Gulf Intracoastal Waterway, which extends the length of the peninsula on the north side, is used primarily for transporting freight; at Bolivar Roads, it forms a water passageway that serves as the marine entrance from the Gulf of Mexico to Galveston Bay.

The Bolivar portion of the waterway belongs to the Galveston District and is maintained by the United States Army Corps of Engineers. Bolivar Peninsula is accessible by land from the Texas mainland only through southern Chambers County. Towns on the peninsula, in addition to Crystal Beach (the only incorporated community), Caplen, and Gilchrist, include Port Bolivar and High Island; independent school districts serving the peninsula include Galveston and High Island. At the southwestern tip of the peninsula at Point Bolivar stands old Fort Travis, named for Alamo hero Col. William B. Travis.

Although Galveston Island has been generally considered the most likely site of the shipwreck of Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca on November 6, 1528, in recent years speculation has developed that the explorer might have arrived on Bolivar Peninsula, near High Island. Indians occupied parts of the peninsula during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and probably much earlier. Atakapas established a burial ground near Caplen, where flint artifacts have been excavated; Orcoquisas occupied the coastal prairie and passed across the peninsula to Galveston Island; and Karankawas roamed the Texas Gulf Coast in the nineteenth century. According to legend, Jean Laffite's entire pirate crew from Galveston Island sometimes held parties on the peninsula. At least one former pirate, Laffite's cabin boy, Charles Cronea, made his home there at Highland, where he is buried.

In 1815 former Gutiérrez-Magee expedition members Warren D. C. Hall and Henry Perryqqv explored the area, and by 1816 the peninsula served as a "highway" for the overland slave trade between Galveston and Louisiana. Privateer Louis Michel Aury transported slaves across the peninsula along this route. According to various sources, the peninsula was named by either Hall, Perry, Aury (who had a commission from Simón Bolívar), or one of the men accompanying Francisco Xavier Mina, who built an earthwork at Point Bolivar in 1816. Dr. James Longqv built a mud fort called Fort Las Casas at the same site in 1820, and here Jane Wilkinson Longqv spent the winter of 1821–22. In 1836 the peninsula served as a refuge for Galveston Island settlers during the Runaway Scrape, and when provisional president David G. Burnet and his staff moved to Galveston Island, many Galvestonians moved eastward up Bolivar Peninsula. Probably the first permanent settler on the peninsula was Samuel D. Parr, who arrived in 1838 and claimed a league of land beginning at Bolivar Point and extending five miles eastward, but by 1850 fifteen families lived between Point Bolivar and High Island, and by 1885 the peninsula's population had grown to 500.

The North Jetty, at the southwestern end of the peninsula, is one of twin restraining walls built into the Gulf of Mexico to provide a deepwater channel to Galveston. The South Jetty extends into the Gulf from Galveston Island. Work on the jetties began as a construction experiment in 1874, and the major portion was completed only after Congress appropriated funds for the work in 1890. Completion of the system in 1898 made Galveston a deep-sea port for world commerce. The jetties now protect shipping to various cities along the Houston Ship Channel, and are used as fishing spots by many sportsmen.

The Gulf and Interstate Railway, which began operation between Port Bolivar and Beaumont in 1896, hastened area development before going into receivership in 1900, and Port Bolivar became an important freight terminal for the Santa Fe Railway, which acquired assets of the rebuilt Gulf and Interstate in 1908. Though destruction of rail lines in the Galveston hurricane of 1900 prevented the growth of Port Bolivar and further damage resulted from the hurricane of 1915, the Santa Fe provided rail service from Port Bolivar to High Island until 1942. Later, the Gulf, Colorado and Santa Fe leased track on the peninsula. Ferries and barges moved cargo-filled freight cars from Point Bolivar across Bolivar Roads to Galveston Island and the Galveston wharves and transported people on excursions every weekend. Free public ferries between Galveston Island and the peninsula operated under the auspices of the State Highway Department after 1933.

Once an important agricultural and ranching area known as the "breadbasket of Galveston" and the "watermelon capital" of Texas, Bolivar Peninsula also enjoyed a brief oil boom centered near High Island. In the 1990s it had an estimated permanent population of 4,000, increased by hundreds of vacation-home owners and summer and weekend visitors seeking recreational activities, which included swimming, sunbathing, fishing, hunting, beachcombing, shell hunting, and bird watching. Though many workers were employed on the peninsula, others commuted to jobs in Galveston, Beaumont, Port Arthur, and other cities to the east.

Important man-made features on the peninsula include Bolivar Lighthouse, near its western end. Two areas of national significance to birdwatchers—the Houston Audubon Society's Louis Smith Bird Sanctuary in High Island and Bolivar Flats near Port Bolivar—offer migrating birds their first landfall as they reach North America from homes in Central and South America. The area is also home to tens of thousands of native shore birds. Bolivar Peninsula Habitat Development Site, a seventeen-acre tract, was developed by the United States Army Corps of Engineers and Texas A&M University.

Information from the Handbook of Texas Online

The Bolivar portion of the waterway belongs to the Galveston District and is maintained by the United States Army Corps of Engineers. Bolivar Peninsula is accessible by land from the Texas mainland only through southern Chambers County. Towns on the peninsula, in addition to Crystal Beach (the only incorporated community), Caplen, and Gilchrist, include Port Bolivar and High Island; independent school districts serving the peninsula include Galveston and High Island. At the southwestern tip of the peninsula at Point Bolivar stands old Fort Travis, named for Alamo hero Col. William B. Travis.

Although Galveston Island has been generally considered the most likely site of the shipwreck of Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca on November 6, 1528, in recent years speculation has developed that the explorer might have arrived on Bolivar Peninsula, near High Island. Indians occupied parts of the peninsula during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and probably much earlier. Atakapas established a burial ground near Caplen, where flint artifacts have been excavated; Orcoquisas occupied the coastal prairie and passed across the peninsula to Galveston Island; and Karankawas roamed the Texas Gulf Coast in the nineteenth century. According to legend, Jean Laffite's entire pirate crew from Galveston Island sometimes held parties on the peninsula. At least one former pirate, Laffite's cabin boy, Charles Cronea, made his home there at Highland, where he is buried.

In 1815 former Gutiérrez-Magee expedition members Warren D. C. Hall and Henry Perryqqv explored the area, and by 1816 the peninsula served as a "highway" for the overland slave trade between Galveston and Louisiana. Privateer Louis Michel Aury transported slaves across the peninsula along this route. According to various sources, the peninsula was named by either Hall, Perry, Aury (who had a commission from Simón Bolívar), or one of the men accompanying Francisco Xavier Mina, who built an earthwork at Point Bolivar in 1816. Dr. James Longqv built a mud fort called Fort Las Casas at the same site in 1820, and here Jane Wilkinson Longqv spent the winter of 1821–22. In 1836 the peninsula served as a refuge for Galveston Island settlers during the Runaway Scrape, and when provisional president David G. Burnet and his staff moved to Galveston Island, many Galvestonians moved eastward up Bolivar Peninsula. Probably the first permanent settler on the peninsula was Samuel D. Parr, who arrived in 1838 and claimed a league of land beginning at Bolivar Point and extending five miles eastward, but by 1850 fifteen families lived between Point Bolivar and High Island, and by 1885 the peninsula's population had grown to 500.

The North Jetty, at the southwestern end of the peninsula, is one of twin restraining walls built into the Gulf of Mexico to provide a deepwater channel to Galveston. The South Jetty extends into the Gulf from Galveston Island. Work on the jetties began as a construction experiment in 1874, and the major portion was completed only after Congress appropriated funds for the work in 1890. Completion of the system in 1898 made Galveston a deep-sea port for world commerce. The jetties now protect shipping to various cities along the Houston Ship Channel, and are used as fishing spots by many sportsmen.

The Gulf and Interstate Railway, which began operation between Port Bolivar and Beaumont in 1896, hastened area development before going into receivership in 1900, and Port Bolivar became an important freight terminal for the Santa Fe Railway, which acquired assets of the rebuilt Gulf and Interstate in 1908. Though destruction of rail lines in the Galveston hurricane of 1900 prevented the growth of Port Bolivar and further damage resulted from the hurricane of 1915, the Santa Fe provided rail service from Port Bolivar to High Island until 1942. Later, the Gulf, Colorado and Santa Fe leased track on the peninsula. Ferries and barges moved cargo-filled freight cars from Point Bolivar across Bolivar Roads to Galveston Island and the Galveston wharves and transported people on excursions every weekend. Free public ferries between Galveston Island and the peninsula operated under the auspices of the State Highway Department after 1933.

Once an important agricultural and ranching area known as the "breadbasket of Galveston" and the "watermelon capital" of Texas, Bolivar Peninsula also enjoyed a brief oil boom centered near High Island. In the 1990s it had an estimated permanent population of 4,000, increased by hundreds of vacation-home owners and summer and weekend visitors seeking recreational activities, which included swimming, sunbathing, fishing, hunting, beachcombing, shell hunting, and bird watching. Though many workers were employed on the peninsula, others commuted to jobs in Galveston, Beaumont, Port Arthur, and other cities to the east.

Important man-made features on the peninsula include Bolivar Lighthouse, near its western end. Two areas of national significance to birdwatchers—the Houston Audubon Society's Louis Smith Bird Sanctuary in High Island and Bolivar Flats near Port Bolivar—offer migrating birds their first landfall as they reach North America from homes in Central and South America. The area is also home to tens of thousands of native shore birds. Bolivar Peninsula Habitat Development Site, a seventeen-acre tract, was developed by the United States Army Corps of Engineers and Texas A&M University.

Information from the Handbook of Texas Online

Like Keep Bolivar Beautiful on Facebook and Follow the page to see photos and keep up with events and our progress.

close

Mail your contribution to:

Keep Bolivar Beautiful • PO Box 2475 • Crystal Beach, TX 77650

Email: info@keepbolivarbeautiful.org